You Don't Get Pascal’s Wager

Philosophy's least-understood argument deserves better.

Sir, it’s happened again: someone has posted about how Pascal’s Wager actually means that we should all be Muslims.

If you’ve spent enough time floating around social media, you have probably seen someone present an interpretation of the Wager to this effect: if your main reason for belief is the benefits of heaven or risk of hell, then Christianity seems like a bad choice. Its vision of hell is ambiguous and many theologians argue that non-Christians can be saved—so why should any rational bettor choose Christ?

For the devoutly Christian Pascal, shouldn’t this be the end? Pack it up—either the argument doesn’t work or it tells you to abandon your beliefs. How did he miss this?

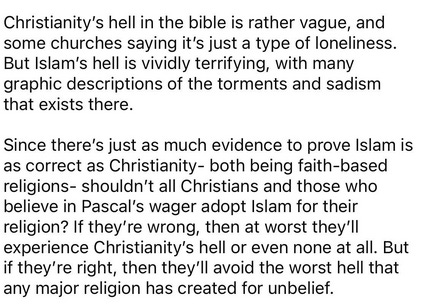

And every time I see a post to this effect—whether it’s this argument about the multiplicity of religions, Christians arguing that it undermines Christianity, or iffy Pascal readers claiming it was a joke—I begin banging my head off the wall and yelling that this is not how to interpret the Wager. It’s not some argument about your best shot at infinite pleasure. It’s a nuanced picture of the many sides of human reason and a means of escaping the doubting calculus of reason. The original Wager illuminates the nature of human belief—these alternatives flatten and deform it.

I do not believe I can stop people from running amok with their bad interpretations of the Wager. But if I can just get one person to see the Wager for what it is, I count that as a success.1

There is a small—but non-zero!—chance that by subscribing, you will gain an eternity in heaven. The cost is zero (unless you want to pledge some support); the upside is infinite. As such, the only rational choice is to subscribe.

A Brief Exposition

As typically stated, the argument is something like this: you should believe in God because that’s the most useful option. You don’t know that God is real, but think about it rationally for a second. If God doesn’t exist, then belief carries a small penalty—obeying religious laws, avoiding a few earthly pleasures, and so on—and might even bring some joy regardless.2 In this world where God doesn’t exist, disbelief carries some limited benefits: earthly pleasures, unrestricted choices, etc. etc.

But if God exists, the calculus is overwhelmingly obvious. Belief in God carries an infinite benefit—eternal joy in heaven—and disbelief leads to infinite suffering in hell. If God’s reality has any nonzero probability—and, given the impossibility of a disproof, there must always be a chance—then a rational actor needs to believe in God. Anything else would be ridiculously irrational.

Such is the cold, mercenary logic driving Pascal. Believe in God because it’s useful. Truth and morality are secondary concerns.

This is not a popular argument. Not among philosophers, not among theologians, and not among us third-estate readers. The objections are many: reason cannot grasp God in full. A life of faith is a quiet, personal sacrifice made in pursuit of goodness. Pascal reduces all of this to the simple logic of investments and returns: God is positive EV! God is a good bet!

And a Christian might argue that this sort of belief in God is actually a sin. You can’t just enter into contract negotiations with the Creator of the Universe—to do such is prideful, immoral, and a path to perdition. So even if the basic logic of the Wager were rational, you would be a fool to follow it—you’re undoing all the benefits you might have otherwise earned.

Two questions for the reader: first, to set up my second question, you probably have a take on Pascal’s Wager. What is it?

Second and more importantly: have you actually read any Pascal? Whether the Pensees (the unfinished collection of notes and essays, including the Wager, that he intended to form a complete work of apologetics) or any of his other philosophical writings? Half credit if you know his work in math or physics.

Because I’d wager most people with a take on the Wager haven’t read a lick of Pascal—which I get, because the Pensees are a slog to get through and the Wager is fertile ground for quick takes and fun arguments—and thus haven’t thought about how weird it is that Pascal supposedly believes this. Because Pascal, far from a cold rationalist, has basically zero faith in human reason’s power to choose the good.

Pascal was an adherent of Jansenism, a Catholic movement that claimed to be absolute followers of St. Augustine’s teachings—nothing more, nothing less. What resulted was a controversial theological position that critics argued denies free will any role in salvation. As these critics presented it, Jansenists contend that God’s grace must be entirely irresistible and necessary for salvation, such that the only way to be saved is for God to choose you and such that anyone not chosen is guaranteed damnation—pretty similar, you’ll notice, to Calvinist predestination. This position was condemned as heresy.

Pascal, like many defenders of the movement, denied that Cornelius Jansen (the thinker who had started the movement with his book Augustinus) ever argued for this. Still, he certainly agreed that man’s will is too weak to find its way to God through reason: “Anything founded on sound reason is very ill-founded,” Pascal wrote.3 As a matter of fact, “Men are wholly occupied in pursuing their good…[but] they have nothing but human fancy and no strength to make its possession secure.”4

Pascal believed that humanity is defined by a paradox: our potential for absolute greatness and our practical depravity. We can be elevated to the greatest of heights, yet we are typically pathetic, sinful, and weak. On our own, we are nothing—yet with God, we can be everything.

And time and time again, Pascal emphasizes that we as Christians need evidence. “I should not be a Christian but for the Miracles, says St. Augustine,” notes Pascal.5 Pascal speaks of this need for miracles many times in the course of the Pensees: we are not going to believe just because of reason.

If you know one thing about Pascal, it’s probably the Wager. If you know a second thing about Pascal, it’s probably his conversion story. Pascal was not much of a Christian in his younger years, briefly identifying with the Jansenists in his 20s but mostly ignoring religion. This changed at about half past ten on November 23rd, 1654 —we know this so precisely because of a note Pascal sewed into his jacket to keep with him forever. That evening, Pascal was overcome by an inexplicable mystical experience—a “night of fire” as it’s commonly described—and wrote passionately that he would never again forget God. This was the inspiration for the Pensees—and, as such, for the Wager.

Yet Pascal’s conversion was clearly absolutely nothing like the rational calculus proposed by the Wager. His life and philosophy contradict this notion of mercenary faith that’s since defined his legacy. How can we reconcile the two?

I think I’ve done enough to demonstrate why it’s implausible that Pascal intended this interpretation. Now, I’d like to show you a better one.

The Heart of the Wager

Before I’d actually read the Pensees, I was exposed to a new view of the wager by the late, great American pragmatist Nicholas Rescher, whom I will describe as a mentor since my reading group emailed with him a bit. His obscure book (Rescher wrote over a hundred books—the vast majority are obscure) Pascal’s Wager: A Study of Practical Reasoning in Philosophical Theology offers, in my view, a far better reading of the Wager.

Rescher’s goal is not solely to defend Pascal or correct erroneous interpretations, though he does so regardless. Critics’ “charges of moral insensitivity and other such high-minded complaints…are based on a total misunderstanding of its aim and import.”6 A typical reading, Rescher contends, ignores its actual content in favor of the digestible, easily criticized version we receive.

Pascal, Rescher contends, is not making this argument in a vacuum. Rather, he stands apart from the Cartesians and Thomists of his time who focused on theoretical proofs for God. Their concern was demonstrating God’s existence through argument.

Yet for Pascal, who saw human reason as insignificant beside God, such argument is useless. “Reason cannot decide this question. Infinite chaos separate us…Reason cannot make you choose either, reason cannot prove either wrong.”7 Our concern cannot be with truth, because the truth of God is beyond us. We must think about actions—and, as such, we must move away from theoretical reasoning to practical reasoning. We have to ask what to do, not what the world is really like. As Rescher presents it, the question is now, “Should we accept that [God] exists—is it appropriate to endorse this position?”8

Mere uncertainty is not acceptable—in practical reasoning, “to suspend judgment is…to resolve the issue in the negative.”9 Not making a choice means choosing disbelief. You must decide. So if reason can’t prove God to us, where do we turn?

Well, we wager. Reason demands certainty and calculus. It demands definite returns and sensibility. Yet religion seems nonsensical: here’s an uncertain proposition that I cannot prove and that demands a meaningful sacrifice on my part—Rescher contends that Pascal was targeting the intelligent libertines of his day, the wealthy, learned men who neglected religion. Reason tells them that Christianity is a nonsensical way to live. Why sacrifice all that for an uncertainty?

The conclusion of the Wager is not, “Therefore, God exists,” or even, “Therefore, I (as someone who has followed and accepted this argument) believe in God.” It is instead, “Therefore, belief in God is prudent.” As self-interested beings, believing in God makes sense. This, Pascal contends, does not reduce us to mercenaries of faith. You have to make a choice—either believe or don’t—so the fact that you have thought about self-interest and chosen belief is no more selfish than to do the same and choose disbelief.

And once we have completed this work—demonstrating that belief in God is warranted by reason—we can finally escape the insufficiencies of reason. The Wager came to meet humanity in our vain, calculating ways. Now, we emerge into the real domain of faith: the heart.

“The heart,” Pascal writes, “has its reasons of which reason knows nothing…It is the heart which perceives God and not the reason.”10 It is this intangible, irrational sort of passion that is meant to contend with God—not merely our reason. “Neither Mind [i.e., reason] nor Heart can force the other’s hand,” Rescher contends.11 But while the heart is inclined to believe,12 the mind’s natural path is skepticism and calculus.

Yet through the Wager, heart offers mind “an appeal made in its own terms” that shows why it should follow along in belief.13 The hesitant Christian encounters God in inexplicable moments—in a beautiful work of art, in the powerful sound of the organ, in a poignant verse of scripture—that cannot command the mind to think God exists but can lead the heart to feel that God exists. The content and nature of this feeling is ineffable—just like Pascal’s night of fire—but following such an experience, the heart cannot help but believe this.

We think of the Wager as the mind taking the heart hostage: reason says to belief, “You had better follow along if you don’t want to burn in hell forever!” Pascal’s approach is the exact opposite: it’s the heart saying to the mind, “We can never be certain of God’s existence. But I still believe, and you know that it benefits both of us.” Pascal’s Wager does not leverage reason except to disarm it. It demonstrates that we have no need to wait for a definitive proof of God to live as reasonable religious men.

And I’d like to note one final argument from Rescher: the many-religions objection is irrelevant. It misinterprets Pascal’s audience and target:

[T]he person who is realistically worried about all these myriad possible jealous gods is indeed going to find Pascal’s Wager unconvincing. But the fact remains the argument is simply not addressed to this person (if such there be). It is addressed to those nominal Christians, whose name is legion, who do indeed espouse the god-conception on which the argument is premised.14

Pascal isn’t trying to tell random atheists to be Christians. He’s trying to ask uncertain and indifferent Christians whether their choices make any sense. Clearly, it contradicts the heart, since they believe in God yet ignore the practice. Clearly, it contradicts reason, since a cunning Christian would be vying for heaven. Your actions are nonsense—if you hold these beliefs, you’re making a bet that will always lose!

I lack the power to stop the endless tide of Wager misinterpretations. But I hope that you now understand Pascal’s actual meaning: not that we ought to live as mercenaries in service of God, but that our heart and mind demand two very different things. The Wager calms the mind so that the heart may contend with God as it must.

Your mind may revolt against subscribing. Yet clearly your heart is inclined towards it seeing as you read this far. Appeal to your selfish reason and subscribe for a chance at infinite utility (a free subscription offers a countable infinity; paid offers an uncountable infinity):

For smaller, earthly benefits, you may consider sharing.

That one person will hopefully be a real-life friend of mine who sends me new Wager arguments every few months and who will be receiving this article promptly.

As Pascal writes, “Now what harm will come to you from choosing this course? You will be faithful, honest, humble, grateful, full of good works, a sincere, true friend…It is true you will not enjoy noxious pleasures, glory and good living, but will you not have others?” P. 125, fragment 418. I’ll be citing the 1995 Penguin edition translated by AJ Krailsheimer, because that’s what I found for cheap at a bookstore once.

P. 6, 26.

Ibid. P. 7, 28.

Says Patrick. Ibid. P. 53, 169.

P. 2. There’s only one edition, so not gonna bother clarifying that.

Pascal, p. 122, 418

Rescher, P. 7

Ibid.

Pascal p. 127, 423, 424.

Rescher p. 101.

Rescher has a whole decision matrix showing the preferred preferences of Mind and Heart and why Heart should always choose belief to maximize its returns. It’s pretty funny, but I also think it’s pretty nonsensical. You can find that on page 102.

Ibid. 103

Ibid. 101

Just @ me next time